|

|

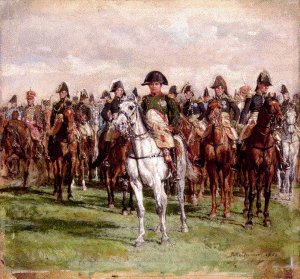

Napoleon and his Marshals - A Painting by Meissonier

Before fighting the Emperor himself during the Waterloo Campaign, Arthur was entitled to affront almost every Marshall of the Empire and a waste choice of most famous French Generals! Sure, he handled them all; some were difficult adversaries, others obviously were much easier to handle. To list them all would go beyond the intent of my WebSite! Interested readers are encouraged to consult the excellent "The Napoleonic Source Book" of Philip J.Haythornthwaite (published by 'Arms and Armour' in 1996 in a paperback edition under ISBN 1-85409-287-1) or to refer to some of those WebSites, which I cite on my page 'Further Reading and Links'.

|

Michel is my absolute favorite! Not so much because he was the most brilliant of Napoleons Marshals (he was definitifely not) or because of his 'sobriquet' The Bravest of the Brave , but simply because emotionally speaking, I find him appealing: Born in Saarlouis and clearly of German descent and origines, he became a fervent Frenchman by choice. Nothing destined him for this career of arms - if not his father's own past as a soldier of the Bourbons, who after having fought as a NCO through the Seven-Years War, returned home, established himself, married a woman of the 'petit bourgeoisie', did well enough in his trade to send all his children of to respectable schooling and did not intent to have his youngest, Michel, take up arms. Michel, who did well in his education was sent of to a Saarlouis notary to learn this respectable profession (This is the reson, why General and Marshal Ney later on wrote so well and with such precision!) But Michel could not cope with sitting in an office, so off he went to work in a mining enterprise close to the border, where his task was somewhat that of a supervisor and economist. For two years, until his 18th birthday he handled this life, but then - Revolution had not yet broken out - the calling of the drums was stronger then fatherly advice (" In the army of the King, a man like you will never go beyond Sergeant's rank! ") Nevertheless, Michel signed up, went into somehow cold terms with his father for a couple of years and soon became a fine horse soldier (He enlisted as a Hussar in 1787)! Even in those days, when only noble origins made a man an officer, he was remarked and it did not take him long to raise to NCO's rank. Then Revolution broke out and Michel fervently subscribed to its ideals: Commissioned already in 1792, he was already a Brigadier General in 1797 and a General de Division by March 1799. He owed much of his ascension to his intelligence, skills learned when still apprentice with the Saarlouis notary and courage. His 'godfather' Moreau saw quickly what stuff the man from Saarlouis was made off! He served in the northern and Rhine theatres and thanks to diplomacy and fluent German, he performed sucessfully in Switzerland, where appart fighting he also had the task of negociator. In 1802, Ney commanded the French armies in Switzerland. It was at this moment that he first came in contact with Napoleon Bonaparte and gradually the ardent republican modified his political beliefs. Josephine de Beauharnais in those days carried out a matchmaker's masterstroke, introducing the brilliant officer to a friend of her daughter Hortense - Aglae Auguie) Following a stormy first encounter and a reproach of the young woman, that he should cut of his old-fashioned ponytail, the two of them married! Apart from being almost until the end Napoleon's most loyal subordinate, he was also the happiest Marshall of France in his private life. He and Aglae where extremly devoted to each other and she carried him four sons, who were all particularly attached to their father. After Ney's death sentence, Aglae fought on until the very moment she was informed that her husband had been shot. Afterwards, also she underwent extreme hardship (her only secure came from Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, then Crown Prince of Sweden, who provided her with a pension and Ney's sons with officers' commissions in the Swedish Army) she carried through her battle for Michel's rehabilitation and finally won it in 1832.

I will not extend myself on the battles and campaigns of Ney - this is well known to everybody - nor on his quintessential role in Napoleons first abdication, nor on the fact, that his untiring efforts and generalship saved the remenants of the Grandee Armee after the Russian disaster of 1812. I want just to conclude upon two remarks: After Waterloo, Napoleon and many others tried to soil the 'Rougeaud's" reputation, pretending that he was the cause of the defeat of France: This is total rubish! Ney performed well, but the communication with Napoleon was very difficult, due to the fact that he received his command only on 12th June 1815 from the Emperor and was not fully introduced to Bonaparte's plans of campaign and intentions. The second point is the accusation, that Ney was unresponding and lethargic at Quatre Bras against Wellington: This is rubish, as well! Ney, this day was deprived of troops, Napoleon had promised to him and therefore could not execute his battle strategy in the same manner, he intended too, while on the other side Wellington finally got hold of his supporting rear which had been delayed on their march. Wellington brought these troops with sped and acuracy into action, while Ney found himself suddenly outnumbered! It was a unholy situation for both adversaries and in the evening it was simply proven that Michel on the 16th of June was the more luckless commander.......................

Perhaps, if you are now interested in this soldier, you will click my link into Projects. There you can find, what I want to write about 'Le Prince de la Moskwa'.

|

He could claim to have saved the Republic by the victories at Wattignies

(1793) and Fleurus (1794). Being a modest, unambitious man, he did not boast of

it. The son of a surgeon of Limoges, in central France, Jourdan enlisted when

only 16 years old. His regiment served in America . After 6 years' service he

went back to Limoges, married a dressmaker, and set up as a small-scale linen

merchant.

In 1790 his neighbours elected him captain in the local national guards. A year

later he was a lieutenant colonel of Volunteers; in 1793 he was in command of

the the Armee du Nord in place of General Jean Houchard, who had been arrested

and soon executed for having won a battle but not pursuing as energetically as

the "Representatives of the people" with Nord thought he should.

Houchard's predecessor, General Adam de Custine, had been "chopped"

for reasons logical only to frightened politicians, so Jourdan knew that he

himself stood in the shadow of the guillotine. Squat, fat, and cheerful, Jourdan

did not look the hero. But he was brave, energetic, and self-confident,

something of an organiser and also obstinate. Beaten one day, he was ready to

try again.

He was a sincere patriot, somewhat of the Jacobin persuasion, close in spirit to

France's political rulers of the moment. His battles tended to be messy,

help-yourself affairs, but he had superior numbers and usually managed to make

them count. Yet he soon developed enough political enemies - for example, by

insisting that soldiers must have shoes for winter campaigning - to be relieved

in early 1794. He reopened his Limoges shop and put his general's uniform on

display. He was recalled for further service during 1794-96 and 1799. Initially

successful, he then met defeat at the hands of the Archduke Charles. His

self-confidence suffered. Between campaigns, however, he sat in the Council of

the Five Hundred and had a large part in designing the sensible 1798

conscription law.

Jourdan did not oppose Napoleon's 1799 coup. Thereafter, aside from the command

of Besancon fortress during the Hundred Days, he had no active duties, but

Napoleon made him military advisor to Joseph in Naples and then in Spain. It was

a frustrating assignment, Joseph being disinterested in matters military and a

coward to boot. Jourdan gave good advice on occasion, but nobody listened.On the

eve of the Battle of Vitoria, Joseph was so obstinate that Jourdan retired to

bed with a fever, while Napoleons brother -the next day - would lose a kingdom!

Louis XVIII made him a count in 1818. Eventually the great revolutionary soldier faded away, almost forgotten..............

|

Born near Nice, then a part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, he knew a harsh

childhood. His father dead, abandoned by his mother, he worked in an uncle's

soap factory until he ran away to sea when he was thirteen.

In 1775 he enlisted in the French Army's Royal Italian Regiment, rising to

regimental sergeant major in 1784. Denied further promotion because of his

plebeian birth, he left the service in 1789, married, and became a local grocer.

In 1791 he enlisted in a Volunteer battalion; in 1793 he was a general of

division.

He had a major part in the Italian campaigns through 1797: A rough-and-ready

commander, scrambling on his hands and knees across sharp ridgelines, showing

his men how to slide down snowfields, lending a hand at carrying knocked-down

cannon over a difficult pass, he was "hard on his men, but equally hard on

himself; sober … great strength of character, indefatigable, on horseback day

and night along the steepest and most dreadful roads, however vile the weather;

decided, brave, full of self-pride and ambition, obstinate to excess, never

discouraged."

But he was so careless in administrative matters that he managed to produce a

soldiers' strike in Rome in 1798.

His 1799 campaign in Switzerland against Austrians and Russians was a true

masterpiece of calculating patience and sudden aggressiveness.

Uninterested in politics, he accepted Napoleon's coup d'etat, then won further

fame by his defense of Genoa in 1800.

His 1805 campaign against the Archduke Charles in northern Italy was no credit

to either of them. In 1809 he was a marvel of tactical skill and determination,

covering the French withdrawal after Aspern-Essling, holding the weak French

left flank at Wagram. Too injured to ride after his horse fell with him, he led

his troops from his carriage.

This was however the last breath of wind of a dying tornado. Napoleon despatched

Massena - his most experienced marshal in independent command and mountain

warfare - off to Spain to dispose of the Duke of Wellington.

Massena was now war-weary in soul and body. He left even the most vital

reconnaissances to his subordinates, moved slowly and indecisively, did not

discipline his insubordinate corps commanders. The campaign was a failure, and

the Emperor replaced him with Marmont. But Wellington remembered him with

respect: "Massena is an old fox, and as cautious as I am." Prematurely

aged and sick, Massena then went on the shelf.

In 1814 many were shocked to discover that he was not a Frenchman and the

Bourbons made him undergo official naturalization to keep his commission!

Massena was a small man with an expressive Italian face. He carried his head

high, and there was something of an eagle in his glance. His physical courage

was absolute; his moral courage matched it. He read with difficulty and

therefore never improved his education. Besides soldiering, he had two

interests: money and women not always in that order. He always remained a

looter. Napoleon rewarded his services handsomely and repeatedly but never could

satiate his appetite. The Emperor balanced the books by ordering large chunks of

Massena's "savings" transferred to the army paymaster. With women as

with money, Massena was discreet, even though he openly took a Madam Lenormand ,

disguised as a hussard with him into Spain in 1810, spending his time more with

her then with his official duties.

He was a leader by instinct, but being uneducated he needed the stimulation of

actual combat to express himself. When necessary, as at Genoa, he shared his

men's hardships. The titles Napoleon gave him - Duke of Rivoli, Prince of

Essling - were battle honours. The revolution more aptly had christened him

" L'enfant cheri de la Victoire" (Victory's beloved child.)

4. Born to Betray - Auguste-Frederique-Louis Viesse de Marmont

|

Soon to come - A Portrait of Marmont

Cadet of the marshals he was out of the petty nobility so common in

northern France. Well brought-up, he was a new-hatched second lieutenant in

1791. Graduating from the Metz artillery school in 1793, he was ordered to

Toulon, where a rising young artillery officer named Napoleon Bonaparte picked

him as one of his aides-de-camp.

During Napoleon's later period of disgrace in Paris, Marmont (unlike Junot) left

him for service on the Rhine frontier, but was recalled when Napoleon took

command of the Army of Italy. He served excellently as a staff and artillery

officer there and in Egypt but proved a prima donna, always clamouring that

nobody sufficiently appreciated his work. Promoted to general of division in

1800, he rendered effective service for two years as inspector-general of

artillery but suffered a severe contusion of the ego when he was not made one of

the 1804 marshals.

After competent service as a corps commander in 1805, he became the civil and

military governor of France's new Dalmatia provinces. There he built the first

roads and public works that back country had seen since Roman times; ruined

years of painstaking Russian infiltration and one Russian expeditionary force;

brought Turkish raiding under control; kept his troops healthy; and dealt justly

with half-savage hill clans. (A suggestion of financial irregularities sometimes

tinged those accomplishments, bringing Imperial warnings.)

Summoned north in 1809, Marmont made a remarkable 300-mile march through

frequently roadless country, scattering two Austrian forces, but clinging to his

independent status and ignoring Eugene's orders. His baton was accompanied by a

scathing Napoleonic critique of his sins of omission and commission.

Napoleon transferred him to Spain after Massena's failure there in 1810. He

arrived with 300 horses, 100 red-liveried domestics, and a long train of

vehicles - an entourage which used up as much food and forage as a calvary

regiment. He accomplished wonders rebuilding the broken-down French forces and

for more than a year became a nightmare for Wellington; skillfully sometimes

outmarching, sometimes outmaneuvering the Sepoy-General. But a moment's

overeagerness at Salamanca (1812) left an opening for the Irishman's sudden

counterstrike (and cost Arthur his lunch -tells us the legend- as he threw away

the chickenleg he was munching, to kick a hell out of Auguste-Frederique......).

As it came on, Marmont took a crippling wound, losing not only an arm but also

all his restauration work done with the French forces in Spain went with the

wind.........Having been only second victor of the day, he heavily felt

Napoleons anger.

Thereafter -having recovered from his wound- he fought through 1813 and 1814 in

Germany and France, often with success - until, in a fit of discouragement, he

went over to the Allies with his whole army, causing finally Napoleon -who had

hoped upon his help to hold Paris - to abdicate for a first time at Fontainbleau

in April 1814.

Marmont, having been created the Duke of Ragusa by Bonaparte also generated a new French word with this act: 'raguser'- this means 'to betray'!

One of the most intelligent and best educated of the marshals, Marmont

also surpassed most of them as an administrator and organiser. As a tactician he

was courageous, imaginative, quick, and deadly. His vanity rendered him

ungrateful to superiors and subordinates alike, but he was not meanly selfish:

In 1815 he risked the Bourbon's anger in an attempt to save Antoine Lavalette

from execution. With all his abilities, there was an unsteadiness about him;

periodically he was seized - sometimes at most unfortunate moments - by spasms

of depression or carelessness.

After Waterloo, cherished by the Bourbons, he lived extravagantly, losing

large sums in attempts at scientific farming. He also diddled with the War

Ministry's files to improve the history of his 1813 operations. In streets and

barracks, his Napoleonic title Duke of Ragusa inspired the new verb raguser - to

cheat, sneak, betray. In 1830, when France rose against its Bourbon King, he

failed to quell the Paris mob and so fled into exile. He had little money left.

|

Soon to come - a Portrait of Soult

Ney's counterpoint and also somewhat a favorite of mine, because he made

Dear Arthur win such an awful lot of battles: Nicolas, nevertheless was

self-contained, intelligent, and calm. A powerful, square-built man, who

suffered the embarrassment of being bowlegged. A severe leg wound, received at

Genoa in 1800, left him with a limp that accentuated this misfortune.

Son of a notary in a small town in southern France, Soult received a good basic

education but had to join the army in 1785 "to live" after his father

died. He was a sergeant by 1791; passing to the Volunteers as an instructor, he

made lieutenant a year later. Fearless and ambitious, he sought promotion even

in those first years, when other officers tried to avoid it lest it bring them

to the attention of the politicians and their guillotine. Trained by Lefebvre

and Massena, he was a general of brigade in 1794, general of division in 1799.

During 1801-5 he was noted for the care with which he trained his men, drilling

and manoeuvring them three times a week, often for 12 hours a day, converting

his IV Corps into the formidable machine that smashed the Austro-Russian centre

at Austerlitz, rolled up the Prussians at Jena, and held against heavy odds at

Eylau.

After his whirlwind Spanish campaign of 1808-9 Napoleon sent Soult to occupy

Portugal, where he promptly involved himself in dark and not too clever

intrigues to become that country's King. Wellington forced him out, and

Soult lost an enormous part of his army by a daring although careless retreat

along mountain trails, poluted with Arthur's allies the 'Guerilla'. Nicolas then

occupied and effectively ruled the south Spanish province of Andalusia ( and

also tried the good wine, good food and exciting hunts of this region!!!!)

Recalled to the Grande Armee in 1813 to support a war-weary and ailing Berthier, he soon was sent back to oppose Wellington after King Joseph's smashing defeat at Vitoria.

He fought - sure indeed brave and gallantly - taking reverse after

reverse in Spain and southern France. Defeated yet never beaten in his spirit to

stand up another time against the Sepoy-General, he always managed to rally his

discuraged ragtag army to fight again and again and again, firing the last shot

for his Emperor, who could give him nothing but his confidence two days after

Napoleons abdication, when he realized that the Battle of Toulouse was

hopelessly lost..........

Minister of War to Louis XVIII during 1814-16, Soult was involved in more

intrigue. Napoleon made him his chief of staff for the Hundred Days, during

which he probably made more errors (I suppose, some of them were even made on

purpose to end it all......) than Berthier had in 18 years. In exile from then

until 1819 (hidden and helped out of the country, where the Ultra-Royalists

claimed his head for high treason by..................doubt it! No, it were the

Prussians who helped Nicolas to save his life. He took exile in Bamberg in

Bavaria) he finally ended in glory: After Charles X fled in 1830, he rebuilt the

disorganised French Army and received the rare title "Marshal-General of

France".

"Imperturbable in good or evil fortune", Ameil remembered,

"observing, seeing all, comprehending all; silent, but hard … He was

attached to no one". In his own way he was fair, never forgetting a

deserving soldier but disliking to be reminded of past promises or past

services. He was an excellent administrator and disciplinarian, took good care

of his troops, and when necessary shared their hardships. He also was a quiet

and skillful looter (Napoleon classed him with Talleyrand in his ability to

"make money out of everything"), building a wonderful collection of

religious pictures from Spanish churches.

He had no strategic sense at all; as a tactician he was very able, but -

especially when operating independently - often too cautious, consequently

missing opportunities. It was said of Nicolas that he could assemble an army of

200.000 men at the given hour on the given spot, but then.........did absolutely

not know, what to do with them! In Spain and in the South of France

Wellington proved time and time again that this saying was correct.

Nicolas' nickname was "Hand of Iron", his soldiers swore it

fitted him like a glove!

soon to come!