A Map of Spain and Portugal from the Days of Wellington's War

"The ball is now at my foot, and I hope I shall have strenghth enough to give it a good kick!"

(Lt.-General Sir Arthur Wellesley to his brother Henry , July 1809)

|

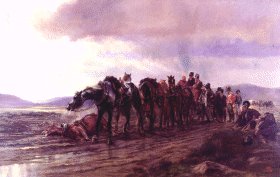

Following its desperate victory over the french at Talavera, Wellington's Army was obliged to retreat back to the Portugese border due to lack of Spanish support and supplies

(Painting by Meissonier)

Victor's 20,000 men, meanwhile, had moved north-east from Merida to Talavera where he hoped to unite with other French forces under General Sebastiani, who had 22,000 men at Madridejos, and Joseph Bonaparte, in command of a further 12,000 men at Madrid. In theory, this would allow the French to field a combined army of around 50,000 men, all of whom were tried and tested soldiers. Against this Wellesley and Cuesta, the Spanish commander, could field 55,000 of whom 35,000 were Spanish.

Wellesley's doubts as to the merits of the Spaniards surfaced fairly soon as did his frustrations when they failed to fulfil any of the promises regarding transport and supplies. And when he rode south to Almaraz to inspect the Spanish Army Wellesley was more than a little disillusioned when he saw the poor condition of their arms and equipment. The seventy year-old Cuesta himself gave little cause for optimism and he adopted a singularly belligerent attitude towards his British ally as a result of which many hours were lost as the two men argued over the strategy to be employed against the French. Eventually, Wellesley and Cuesta agreed to unite their armies at Oropesa, about thirty miles west of Talavera.

The two forces duly met as planned on July 20th and three days later had a perfect opportunity to attack Victor who had yet to meet either Sebastiani or Joseph and who was outnumbered by just over two to one. Cuesta refused to move, however, and the chance was lost although he did agree to attack at dawn on the 24th, although by then, of course, Victor had retired towards Madrid.

Wellesley was naturally furious and when a buoyant Cuesta decided to set off in pursuit of Victor it was Wellesley's turn to refuse to budge. This was with good reason as intelligence reports showed that the French were only days away from uniting which would give them a combined strength of 50,000 men. Nonetheless, Cuesta gave chase and was predictably mauled by Victor's veterans on July 25th.

By July 27th Wellesley had positioned his army a few miles to the west of the Alberche river which flows north from the Tagus just east of Talavera. Later that day he narrowly avoided capture whilst carrying out a reconnaissance from the top of the Casa de Salinas, a semi-fortified building on the left bank of the Alberche. As he peered out in the direction of the French army he just caught sight of a party of French light infantry, stealing around the corner of the building. He rushed down the stairs, mounted his horse and rode hell for leather away from the building followed by a couple of volleys from the enemy infantry. It was the first of a couple of occasions in the Peninsula where Wellesley narrowly avoided capture, the other notable occasion being at Sorauren in 1813.

There was some skirmishing throughout the rest of the day including the celebrated incident during the evening involving four battalions of Spanish infantry who, when apparently `threatened' by some distant French cavalry, let loose a shattering volley before running away at the sound of their own muskets, stopping only to plunder the British baggage train.

That night Wellesley had drawn his army up along a front stretching north to south from the heights of Segurilla to Talavera itself. On the right were positioned Cuesta's 35,000 Spaniards, the right flank resting upon Talavera being the strongest part of the line. The left flank of the British line rested upon the Cerro de Medellin, a large, domineering hill, separated from the heights of Segurilla by a wide, flat valley nearly a mile wide. In front of the Allied position, and directly opposite the Cerro de Medellin, was the Cerro de Cascajal which was soon to become the centre of the French position and between the two hills, running along the valley between them, was a small stream called the Portina.

The sun had long since gone down when at around 10 o'clock, under the cover of darkness, an entire French division stole across the Portina and fell upon the British and German troops, on and at the foot of the Medellin, who were dozing off after a hard day in the field. The French advanced in three columns, one of which got lost and, failing to find any of its objectives, returned to the main French line. The other two columns, however, caused a great deal of panic in the British lines and at one point even occupied the summit of the Medellin after managing to completely pass by Donkin's brigade which occupied the forward slopes of the hill.

It was during this confusion that Rowland Hill almost got himself captured when, riding forward to investigate with his brigade major, he found himself confronted by a number of French voltigeurs, one of whom tried to drag Hill from his horse. The two British officers quickly turned tail and rode off but the brigade major was killed when the French opened fire. Hill then brought forward Stewart's brigade of the 2nd Division, amongst which was the 29th who drove the French from the summit amidst a blaze of spectacular musketry which lit up the night with each volley. The situation was eventually restored and the French returned to their original positions having lost about 300 men, the British losing a similar number.

A single French gun, fired in the gloom at about 5 o'clock on the morning of July 28th, signalled the beginning of the main French attack. The gun triggered off a rippling fire that rolled along the French position from about 60 of their guns. On the Medellin Wellesley's men were ordered to lie down as enemy cannonballs came bouncing in amongst them whilst on the slopes of the hill British gunners worked at their own guns in reply.

From his position high on the Medellin, which was shrouded in smoke, Wellesley could see nothing of what was going on below but the sounds - soon to become so familiar to him and his army - were unmistakable. Large numbers of French tiralleurs were pushing back his own skirmish lines although Wellesley's light companies and riflemen disputed every yard of broken ground. The French came on in three columns, each three battalions-strong, altogether numbering nearly 4,500 men from Ruffin's division. The most northerly of the columns, moving to the north of the Medellin, exchanged fire at long range with the 29th but went no farther. The other two columns, however, hit that part of the British line on the Medellin which was held by Stewart's and Tilson's brigades. As at Vimeiro the French attack was hampered by its formation and the outnumbered British brigades easily outgunned the French columns, sweeping them with fire and forcing them to a standstill. French attempts to deploy into line proved futile and impossible amidst the concentrated, controlled platoon fire from the 29th and 48th Regiments. After just a few minutes those at the back and in the middle of the French columns, unable to see what was happening up front but aware that something very unpleasant was happening to their comrades, decided not to wait and see for themselves but simply melted away to the rear, very few of them having fired any shot in anger. Ruffin's attack had ended in failure and his beaten battalions were pursued for a short distance across the Portina having suffered over a thousand casualties.

The initial French attack having been repulsed by 7am the battle lapsed into a duel between the two sides' artillery. This lasted for just an hour and no more serious fighting occurred for another five hours, during which both sides quenched their thirst in the shimmering heat at the Portina brook and took advantage of the lull to collect their wounded.

At 1 o'clock in the afternoon the peace was shattered by another French artillery barrage that heralded a large-scale infantry assault on the right of Wellesley's line around the Pajar, a semi-fortified farmhouse that marked the junction of the British and Spanish sectors of the Allied line. Laval's division numbered 4,500 men who began to advance across the broken ground and through the olive groves to begin their attack on that part of Wellesley's line held by Campbell's 4th Division.

Again Laval's men attacked in three columns, each three battalions-strong supported by guns, but as had happened earlier in the day his men found Campbell's musketry too hot to handle and the French columns broke and fled before they did too much damage and having abandoned seventeen of their guns. Laval's attack was only the prelude to the main French attack, however, and shortly afterwards some 80 French guns were blazing away at the right centre of the British line in an attempt to soften it up before the main infantry assault which would be delivered by no less than 15,000 seasoned troops under Sebastiani and Lapisse.

It sounds rather repetitive to say that the French columnar formation gave the British line a distinct advantage but that is exactly what happened - again. The twelve French battalions could bring only 1,300 muskets to bear on their British adversaries, some 6,000 men of Sherbrooke's 1st Division, amongst whom were some of the best troops in the army, the Foot Guards and the King's German Legion. The irresistible and pulverizing firepower of these troops was turned on the French to devastating effect and soon enough the French veterans were streaming back across the Portina. Unfortunately, three of the brigades who had seen them off, including the Guards and the Germans, were carried away with their success and, pursuing them too far, were in turn severely mauled by the French, large numbers of whom were still fresh. Sherbrooke's men returned to the British line in a sorry state, particularly the Foot Guards who had lost 611 men.

This misadventure caused a large gap in the Allied centre upon which some 22,000 French cavalry and infantry bore gleefully down with relish. There was no second Allied line and Wellesley could spare only a single battalion to plug the gap. It was a major crisis. Fortunately, the battalion, the 1/48th, was the strongest in the army but it still had to face a French attack of overwhelming numerical strength. The 48th was supported by the three battalions of Mackenzie's brigade which were moved slightly to their left to join the 1/48th. These battalions, numbering around 3,000 men, opened their ranks to let in the survivors of the Guards who formed up behind them and with a great cheer announced their intention to rejoin the battle.

The British troops waited silently in line as the French came noisily on, British 6-pounder guns tearing gaps in their columns as they did so. Lapisse's battalions had advanced to within just fifty yards when nearly 3,000 nervous British fingers twitched on the triggers of their Brown Bess muskets and whole files of Frenchmen came crashing to the ground amidst rolls of thick grey smoke. The shattered French columns shuddered to a halt in the face of the savage onslaught. A series of withering volleys ripped into them at the rate of four every minute and although they stood to trade fire with Mackenzie's men the French could not match the firepower of their enemies. In the face of such an onslaught, in which the Guards and the 14th Light Dragoons joined in, Lapisse's battalions broke and fled back across the Portina leaving some 1,700 of their comrades behind them to mark their failure.

All French attacks to the south of and directly at the Medellin had resulted in bloody failure and the French troops watching from the Cascajal did not relish the thought of tasting any more of such treatment. It was decided, therefore, to test the mettle of Wellesley's left flank to the north of the Medellin, Ruffin's infantry division being the instrument of this test. The nine battalions of Ruffin's division had already been heavily engaged the night before and on the morning of the 28th itself and the men showed little inclination to attack in any positive manner, a reluctance not unnoticed by Wellesley who decided to launch his cavalry against them.

Ruffin's columns advanced amidst heavy shelling from the Allied artillery and when Anson's cavalry brigade, consisting of the 23rd Light Dragoons and 1st Light Dragoons King's German Legion, was spotted advancing along the floor of the valley to the north of the Medellin, the French formed square which provided an even better target for the guns. Anson's cavalry advanced in a controlled manner against the French who were still a good distance away. However, this disciplined ride was not to last for too long, for the 23rd Light Dragoons were about to provide the British Army with the second of its great cavalry fiascos of the war.

For no apparent reason the light dragoons suddenly broke into a full gallop whereas the German light dragoons held back, keeping up a gentle pace. The 23rd Light Dragoons, under the command of Major Ponsonby, suddenly came up against a small, dry river bed which was a tributary of the Portina. The cutting was deep and wide and whilst not the sort of ravine that it has often been called it was, nonetheless, a serious obstacle for a cavalry regiment to negotiate at full speed. The first ranks crashed headlong into the cutting whilst others tried in vain to leap across to the other side. It was a classic `steeplechase' in which scores of men and horses were lost, the majority with badly broken arms and legs. Those who were lucky enough to negotiate the cutting then found themselves vastly outnumbered by French chasseurs who set about the blown and disorganised light dragoons with relish. Ponsonby's men rallied and fought as best they could but they were overwhelmed and forced back to their own lines having lost half of their number. The 1st Light Dragoons KGL, on the other hand, had come on at an easier pace and took the cutting in their stride. Their own attack failed to break any of the French infantry squares and they too retired to their original position. However, the two cavalry attacks, combined with the constant shelling from the Allied artillery, caused Ruffin's wavering division to turn about and return to the Cascajal.

Although there were still three hours of daylight left there was no further serious fighting and as darkness fell Wellesley's men camped on the ground they occupied around the Medellin expecting a resumption of the battle the next day. However, when dawn broke on the 29th the British troops peered out across the valley to see that Victor's army had retired leaving Wellesley in possession of the field.

It had been a bloody battle which had cost the British some 5,365 casualties. The French themselves had lost 7,268. Cuesta's Spaniards had held the right flank of the Allied position throughout the day but had hardly been involved in any of the fighting and their loss was trifling.

The victory at Talavera had earned for Wellesley the title Baron Douro and Viscount Wellington. There were few other comforts to be derived from the battle, however, as captured despatches showed the French to be far more numerous than had been thought. On August 3rd Wellington and his army were at Oropesa but news that Soult was close by at Navalmoral, and in danger of cutting him off from Portugal, prompted a quick retirement upon Badajoz on the Spanish-Portuguese border

|

Lord Wellington in Spain 1814

The advance began on May 22nd 1813 and as the Allied army crossed the Portuguese border into Spain Wellington is reputed to have turned and waved his hat in the air, exclaiming, "Farewell, Portugal, for I shall never see you again." He was right. Wellington left Hill's force on May 28th and joined Graham the following day. By June 3rd his entire force, numbering around 80,000 men, was on the northern side of the Douro, much to the surprise of the French who began to hurry north to meet them. Such was the speed of Wellington's advance that the French were forced to abandon Burgos, this time without any resistance, and the place was blown up by the departing garrison on June 13th. Wellington passed the town and on June 19th was just a short distance to the east of Vittoria which lay astride the great road to France.

The battlefield of Vittoria lay along the floor of the valley of the Zadorra, some six miles wide and ten miles in length. The eastern end of this valley was open and led to Vittoria itself while the other three sides of the valley consisted of mountains although those to the west were heights rather than mountains. The Zadorra itself wound its way from the south-west corner of the valley to the north where it ran along the foot of the mountains overlooking the northern side of the valley. The river was unpassable to artillery but was crossed by four bridges to the west of the valley and four more to the north.

Wellington devised an elaborate plan of attack which involved dividing his army into four columns. On the right, Hill, with 20,000 men consisting of the 2nd Division and Morillo's Spaniards, was to gain the heights of Puebla on the south of the valley and force the Puebla pass. The two centre columns were both under Wellington's personal command. The right centre column consisted of the Light and 4th Divisions together with four brigades of cavalry, who were to advance through the village of Nanclares. The left centre column consisted of the 3rd and 7th Divisions which were to advance through the valley of the Bayas at the north-west corner of the battlefield and attack the northern flank and rear of the French position. The fourth column, under Graham, consisted of the 1st and 5th Divisions, Longa's Spaniards and two Portuguese brigades. Graham was to march around the mountains to the north and by entering the valley at its north-eastern corner was to severe the main road to Bayonne.

Joseph's French army numbered 66,000 men with 138 guns but although another French force under Clausel was hurrying up from Pamplona they would not arrive in time and Joseph was to fight the battle with about 14,000 fewer men than Wellington.

On the morning of June 21st Wellington peered through his telescope and saw Joseph, Marshal Jourdan and General Gazan and their staffs gathered together on top of the hill of Arinez, a round hill that dominated the centre of the French line. It was a moist, misty morning and through the drizzle he saw, away to his right, Hill's troops as they made their way through the Heights of Puebla. It was here that the battle opened at about 8.30am when Hill's troops drove the French from their positions and took the heights.

Two hours later, away to the north-east, the crisp crackle of musketry signalled Graham's emergence from the mountains as his men swept down over the road to Bayonne, thus cutting off the main French escape route. Hereafter, Graham's troops probed warily westward and met with stiff resistance, particularly at the village of Gamara Mayor. Moreover, Wellington's instructions bade him to proceed with caution, orders which Graham obeyed faithfully. Although his column engaged the French in several hours of bloody fighting on the north bank of the Zadorra, it was not until the collapse of the French army late in the day that he unleashed the full power of his force upon the French.

There was little fighting on the west of the battlefield until at about noon when, acting upon information from a Spanish peasant, Wellington ordered Kempt's brigade of the Light Division to take the undefended bridge over the Zadorra at Tres Puentes. This was duly accomplished and brought Kempt to a position just below the hill of Arinez and while the rest of the Light Division crossed the bridge of Villodas Picton's `Fighting' 3rd Division stormed across the bridge of Mendoza on their right. Picton was faced by two French divisions supported by artillery but these guns were taken in flank by Kempt's riflemen and were forced to retire having fired just a few salvoes. Picton's men rushed on and, supported by the Light Division and by Cole's 4th Division, which had also crossed at Villodas, the 3rd Division rolled over the French troops on this flank like a juggernaut. A brigade of Dalhousie's 7th Division joined them in their attack and together they drove the French from the hill of Arinez. Soon afterwards, what was once Joseph's vantage point was being used by Wellington to direct the battle.

It was just after 3pm and the 3rd, 7th and Light Divisions were fighting hard to force the French from the village of Margarita. This small village marked the right flank of the first French line and after heavy fighting the defenders were thrust from it in the face of overwhelming pressure from Picton's division. To the south of the hill of Arinez Gazan's divisions were still holding firm and supported by French artillery were more than holding their own against Cole's 4th Division. However, with Margarita gone the right flank of the French was left unprotected.

It was a critical time for Joseph's army. On its right, D'Erlon's division was being steadily pushed back by Picton, Dalhousie and Kempt, whose divisions seemed irresistible. Away to his left, Joseph saw Hill's corps streaming from the heights of Puebla whilst behind him Graham's corps barred the road home. Only Gazan's divisions held firm but when Cole's 4th Division struck at about 5pm the backbone of the French army snapped. Wellington thrust the 4th Division into the gap between D'Erlon and Gazan, as a sort of wedge, and as the British troops on the French right began to push D'Erlon back Gazan suddenly realised he was in danger of being cut off. At this point Joseph finally realised that he was left with little choice but to give the order for a general retreat.

The resulting disintegration of the French army was as sudden as it was spectacular. The collapse was astonishing as every man, from Joseph downwards, looked to his own safety. All arms and ammunition, equipment and packs were thrown away by the French in an effort to hasten their flight. It was a case of every man for himself. Only Reille's corps, which had been holding engaged with Graham's corps, managed to maintain some sort of disorder but even Reille's men could not avoid being swept along with the tide of fugitives streaming back towards Vittoria. With the collapse of all resistance Graham swept down upon what units remained in front of him but there was little more to be done but round up prisoners who were taken in their hundreds. The French abandoned the whole of their baggage train as well as 415 caissons, 151 of their 153 guns and 100 waggons. 2,000 prisoners were taken.

More incredible, however, was the fantastic amount of treasure abandoned by Joseph as he fled. The accumulated plunder acquired by him in Spain was abandoned to the eager clutches of the Allied soldiers who could not believe what they found. Never before nor since in the history of warfare has such an immense amount of booty been captured by an opposing force. Ironically, this treasure probably saved what was left of Joseph's army for while Wellington's men stopped to fill their pockets with gold, silver, jewels and valuable coins, the French were making good their escape towards Pamplona. Such was Wellington's great disgust at the behaviour of his men afterwards that he was prompted to write to the Earl of Bathurst. It was the letter in which he was to use the famous expression, `scum of the earth'.

The Allies suffered 5,100 casualties during the battle, of which less then 800 were killed, while the French losses were put at around 8,000, but probably many more. The destruction of Joseph's three armies is hardly reflected in this figure, however, and the repercussions of the defeat were far reaching. News of Wellington's victory galvanised the Allies in northern Europe - still smarting after defeats at Lützen and Bautzen - into renewed action and even induced Austria to enter the war on the side of the Allies. In England, meanwhile, there were wild celebrations the length of the country while Wellington himself was created Field Marshal. In Spain, Napoleon's grip on the country was severely loosened and there was now little but a few French-held fortresses between Wellington's triumphant army.

The French Armies, apart from Clausel's corps were now dispersed and making their way unencumbered by discipline, baggage and inspired leadership back into France. Only parts of Maximilien Foy's division continued an effort of coordinated resistance. Graham was brought up by him at Tolosa. Hill blockaded Pampeluna, and Arthur himself now tried to get himself between Clausel and Jacca. But this time Clausel was to quick for the Leopard and got his corps savely over the central Pyreneen passes to Pau.

Only two french garrisons remained - San Sebastian and Pampeluna. Both were blockaded. In the next months Wellington had to spend a lot of time and to spill a lot of ink over General Sir John Murray's disgracefully giving up the siege of Tarragona. But as this had no direct effect upon Arthur's campaigning, we will ignore this and turn to more interesting subjects. He determined to turn the blockading of San Sebastian into a siege and though he was not directly in charge, as always when our Irish General took to Vauban, nothing would go right. At least he called in his experts Dickson and Fletcher to take this one in hand.

Meanwhile the rest of the army and their valliant leader moved uphills into the Pyreneen Mountains to cover the principal gateways between France and Spain. It was a countryside unlikely to whatever they had experienced before. The last few miles from Roncesvalles to St.Jean de Luz and Biaritz are not that high, but damned steep, with well timbered slopes and narrow but fertile valleys and............lots of sheep. And then there is a bewildering multitude of rivers and gorges and grags in this region of the world. Not realy the dream for a Theatre of War!

|

Wellington overlooking the Battlefield of Vitoria

(Chapter 5, Part 3 - "Deep behind the Lines of the Enemy)

Während der Baske seinem gefährlichen Geschäft nachging, starrten der Benediktiner und der irische General sich lange stumm an. Nur in ihren Köpfen gab es Bewegung. Der Krieg war ein großes Spiel. Der, der in diesem Spiel zu List und Tücke griff, gewann für gewöhnlich den entscheidenden Tag. Es gab langfristig angelegte Listen und Tücken. Hierzu zählte Pater Jacks weitverzweigter Spionagedienst. Und es gab einfache Kriegslisten, die aus der Situation und der günstigen Gelegenheit eines kurzen Augenblickes geboren wurden. Eine beunruhigende Information, am richtigen Ort, in der richtigen Feindeshand platziert, zählten hierzu. Arthur und Pater Jack waren dabei, eine kleine Überraschung für König Joseph auszutüfteln!

" Mein Freund, zwei entschlossene Soldaten, bereit als Deserteure im Hauptquartier von General Gazan aufzutauchen und ihm zu berichten, das Sie im Morgengrauen mit einem starken Truppenkontingent nach Norden marschiert seien.......... Ich bin mir sicher, dieser Winkelzug reicht, um Aufregung zu stiften!"

" Und wenn der Comte ihnen nicht glaubt, dann hängt er mir meine beiden entschlossenen Leoparden auf, Jack!" Wellington nickte Robertson zu. Die Idee war natürlich gut. Es gab Deserteure und Deserteure! Die einen verschwanden bei Nacht und Nebel, um nie wieder unter König Georgs Fahnen zurückzukehren, die anderen wurden losgeschickt. Er hatte es in Indien getan, und in Portugal und in Spanien. Er mochte die Methode nicht, doch er würde wieder zwei Freiwillige mit Falschmeldungen in die feindlichen Linien schicken. Langsam stand er vom Tisch auf, zog den Waffenrock glatt, gürtete den Säbel um und verlies mit nachdenklicher Mine sein provisorisches Hauptquartier. Sir Arthur machte sich auf den Weg zum 33.Regiment, um Oberst James Dullmore diskret zu befragen, wer dieses Mal freiwillig die Fahnen Englands hinter sich lassen könnte, um einen französischen General von einer nicht existierenden Truppenbewegung zu überzeugen.

Eine halbe Stunde später, es war noch nicht einmal neun Uhr morgens, befanden sich drei Männer in der kleinen Schankstube. Den Wirt hatten sie fortgeschickt. Alle Türen und Fenster waren sorgfältig verschlossen. Nur eine Kerze erleuchtete den Raum. Genau so, wie Lord Wellington, hatte auch Bonny Augen und Ohren im Feldheer seines Gegners.Um halb elf Uhr ordnete der Oberst der 33.Infanterie eine Überraschungsinspektion an. Alle Männer mussten innerhalb von dreißig Minuten kampfbereit und mit voller Ausrüstung Aufstellung nehmen. Während im Lager des Regiments ein Rennen und Laufen einsetzte, stahl eine unsichtbare Hand Sergeant-Major Howard sein Pulverhorn und sechzig Schuss Munition aus dem Rucksack. Eine andere unsichtbare Hand platzierte eine Geldbörse mit fünf britischen Goldguineas im Marschgepäck des Trommlerjungen Meadows. Auf der Börse waren die Initialen von Oberst James Dullmore deutlich sichtbar eingeprägt.

Pünktlich um elf Uhr, am 20.Juni 1813 war das gesamte 33.Infanterieregiment zur Inspektion angetreten. Mit versteinerter Mine ritt Jamie auf seinem großen, weißen Andalusierhengst vor den Rängen auf und ab. Die Leoparden konnten sich keinen Reim darauf machen, was dieser sonderbare Befehl eigentlich zu bedeuten hatte. Im Angesicht einer großen Feldschlacht, war es nicht üblich, sich mit unnützem, administrativen Geplänkel abzugeben. Doch sie konnten ihren neuen Oberst einfach noch nicht einschätzen: Er war ein ‘Mann aus den Bergen’, er hatte vier lange Jahre einen blutigen Partisanenkrieg gekämpft! Er hatte keine Vergangenheit und er war ein Favorit Lord Wellingtons. Als Kommandeur war er hart, wie ein Diamant. Keiner der Männer hatte ihn jemals lächeln sehen.

Jamie zügelte sein nervöses Pferd genau in der Mitte der Aufstellung. Seine Stimme war schneidend, wie ein Dolch: " Einer in diesem Regiment ist ein Dieb! Einer von Euch hat etwas genommen, was ihm nicht zusteht, denn es ist das Eigentum eines anderen! Meines! Ich dulde keine Diebe in meinem Regiment, genau so wenig, wie ich Männer dulde, die Ihre Pflicht nicht erfüllen, oder die sich im Dienste etwas zu schulden kommen lassen!"

Major Robin Seward war auf seinem Pferd erbleicht. Es war eine geradezu unglaubliche Anschuldigung, die Jamie Dullmore da eben verkündet hatte. Im 33.Infanterieregiment hatte es im Verlauf der letzten Jahre, außer kleiner Verfehlungen keine nennenswerten Probleme gegeben. Doch der Gesichtsausdruck des Obersten verriet äußersten Zorn. Jamie war ein gerechter Mensch! Wenn nicht irgend etwas an dieser Anschuldigung wahr sein würde, er hätte es nie gesagt. Rob kannte Dullmore gut.

" Jeder von Euch wird sein Marschgepäck vor sich stellen! Jetzt!", fuhr der Oberst bitter fort, "Jeder, das heißt, auch die Unteroffiziere!" Dann wandte er sich an Major Seward:" Sir, Sie werden gemeinsam mit Major Coley und Major Fitzpatrick die Rucksäcke durchsuchen!" Seine Augen glitzerten kalt. Seward konnte nicht in ihnen lesen. Er stieg vom Pferd. Die Leoparden hatten alle ihre Tornister vor sich ins Gras gestellt. Es war eine langwierige Prozedur. Das 33.te war ein starkes Regiment mit fast achthundertundfünfzig Soldaten. Dullmore hatte seinen Hengst einem Adjutanten in die Hand gedrückt. Zielstrebig ging er auf Sergeant Price zu. Er sah ihm hart in die Augen, öffnete den Tornister und leerte den Inhalt auf den Boden:" Ein Bajonett und Futteral, ein Pulverhorn und sechzig Schuss, Messegeschirr, eine Decke, zwei Hemden, ein paar Schuhe, ein paar Strümpfe, Bürste, Kamm, Seife, Schreibzeug, zwei Zeltpflöcke, drei Rationen Brot, zwei Rationen Fleisch..." Er schüttelte die Wasserflasche," Gefüllt! In Ordnung, Sergeant, Sie können wieder einpacken!" Dann ging er zum nächsten Sergeanten und wiederholte die Prozedur. Howard war der letzte. Jamie hatte den Inhalt seines Tornisters ausgeleert und angefangen ihn zu überprüfen. Plötzlich hielt er inne, baute sich vor dem Sergeant-Major auf und fauchte ihn an. Sein Gesicht war rot vor Wut:" Howard, sind Sie denn von allen guten Geistern verlassen! Wo sind Ihr Pulverhorn und die Munition?! Der Unteroffizier war erbleicht. Er war ein Perfektionist. Noch nie war es vorgekommen, das auch nur ein Schnürsenkel in seinem Tornister gefehlt hatte. Und nun das Pulverhorn und die Munition! Er war so verwirrt, dass er kein Wort hervorbrachte. Jamie funkelte ihn böse an. Dann packte er ihn am Arm und stieß ihn in die Hände des Regimentsprovost:" Sir, Sie wissen, was zu tun ist! Erinnern Sie ihn mit der Neunschwänzigen an seine Pflicht, als Unteroffizier!" Er blitzte den Sergeant-Major noch einmal an:" Es ist unverzeihlich, im Angesicht einer großen Kampfhandlung sein Pulverhorn und seine Munition zu verschlampen! Sie sind Sergeant-Major gewesen. Nach der Bestrafung können Sie den fünften Streifen von Ihrem Ärmel abtrennen!" Howard wusste nicht, was ihm geschah. Er hatte seine Sprache noch nicht wiedergefunden. Etwa im gleichen Augenblick, in dem Oberst Dullmores Donnerwetter sich über den Sergeant-Major ergoss, erstarrte Rob Seward. Er hatte gerade den Tornister von Trommler Meadows geprüft. Tief unten in dem Gepäckstück hatte seine Hand etwas Weiches, Ledernes ertastet. Vorsichtig zog er es ans Tageslicht. Seine Augen fixierten ungläubig den Jungen. Tommy schien sich keiner Schuld bewusst. Rob hielt eine lederne Börse mit Dullmores Initialen in Händen:"Mein Gott, Kleiner! Was hast Du nur getan?" flüsterte er eher sich selbst zu. Meadows wurde kreidebleich. Genau, wie bei Howard war Dullmore an Sewards Seite, noch bevor der Trommler den Mund auftun konnte. Er glich einem Racheengel: "Sieh an, so jung und schon ein Dieb!", zischte der Oberst," Du weißt, wie diese Armee mit Soldaten verfährt, die ihre Offiziere bestehlen?" Die britischen Landstreitkräfte kannten bei dieser Art von Verbrechen keine Gnade. Ein Kriegsgericht wurde einberufen. Der Urteilsspruch lautete unweigerlich auf Tod durch den Strick. Genau, wie zuvor Howard, wurde jetzt Trommler Meadows grob in die Arme des Provost gestoßen. Dem Jungen liefen Tränen der Angst über die Wangen. Laut hörbar schluchzte er. Rob Sewards Magen krampfte sich schmerzhaft zusammen.

Lord Wellington kam mit Pater Jack Robertson, wie zufällig durch das Lager der 33.Infanterie geritten. Vor dem angetretenen Regiment, den Offizieren, dem Provost und dem weinenden Knaben zügelte er sein Pferd. Seine Mine war genau so undurchdringlich, wie die von Oberst Dullmore. Scharf fragte er den Kommandeur der Einheit:" Was hat das zu bedeuten, Sir?" Seine Stimme verriet nicht die geringste Zuneigung für Jamie. Sie war geschäftsmäßig und kalt. Der Oberst legte die Hand an den Zweispitz:" Mylord, ein schwerer Fall von Diebstahl und ein schwerer Fall von Nachlässigkeit im Angesicht des Feindes und der anstehenden Kampfhandlungen!" Seine Stimme war genau so geschäftsmäßig und kalt, wie die des obersten Leoparden. Arthur nickte ihm zu:" Berufen Sie sofort ein Kriegsgericht ein, Sir und wegen der Disziplinarstrafe.... Ich erwarte, das sie vor dem Tanz mit den Adlern vollstreckt wird. Sie kennen meine Anordnung! Kein Mann, der eine Strafe zu erwarten hat, darf in den Kampf geschickt werden!" Der General wendete sein Pferd. Ein verächtlicher, hochmütiger Blick schweifte kurz über Trommler Meadows und Sergeant-Major Howard. Die Leoparden, die am nächsten standen, hörten, wie ihr ehemaliger Kommandeur seinem Chefspion sagte:" Der Abschaum der Erde, Jack, nichts als der Abschaum der Erde!"

Üblicherweise setzte ein Kriegsgericht sich aus den Offizieren des betroffenen Regiments zusammen. Dullmore hätte als Oberst den Vorsitz geführt, doch da er der Bestohlene und damit befangen war, fiel diese Aufgabe seinem Stellvertreter, Oberstleutnant Elphistone zu, der die 33.Infanterie früher für Wellington kommandiert hatte und der in diesen Tagen, seit Jamies Ernennung, als Stellvertreter fungierte, weil sein neues Regiment noch nicht aus England eingetroffen war. Damit konnte man sagen, der Offizier war ein wirklich neutraler Richter. Trommlerjunge Meadows hatte das Recht auf einen Verteidiger, obwohl sein Fall recht hoffnungslos war. Ein Offizier seiner Wahl übernahm diese Rolle. Tommy bat Robin Seward, sich seiner anzunehmen. Der Major kannte den Burschen gut. Er mochte ihn gerne. Obwohl die Geldbörse in seinem Tornister eine sehr eindeutige Sprache sprach, versuchte er doch das Äußerste. Obwohl er mit der Jugend und dem guten Verhalten des Trommlers argumentierte, konnte er Meadows nicht mehr helfen. Elphistone und seine Beisitzer betrachteten den Fall als klar. Tommy wurde zum Tod durch den Strick verurteilt. Das Urteil sollte vollstreckt werden, sobald Lord Wellington und General-Advokat Larpent gegengezeichnet hatten.

Während das Kriegsgericht den schweren Diebstahl aburteilte, wurde in der Mitte des Lagers der 33.Infanterie ein Gerüst aus drei Unteroffizierslanzen errichtet. Für seine Verfehlung erwarteten Sergeant Howard, außer dem Verlust seines fünften Streifens, noch fünfzig Hiebe mit der Neunschwänzigen Katze. Das gesamte Regiment musste bei der Bestrafung zusehen. Das Kriegsgerichtsverfahren gegen Meadows beendet, begaben sich alle Offiziere des Regiments zum Ort der Handlung. Man brachte den Sergeanten zu dem Gerüst. Sein Oberkörper war bereits entblößt. Er ging sehr aufrecht. Er blickte weder nach rechts, noch nach links. Howard war sich keiner Verfehlung bewusst. Irgend jemand hatte ihm - aus Rachsucht, oder Bosheit - einen bösen Streich gespielt. Zwei Unteroffizierskameraden banden seine Hände an der Querstrebe fest. Es war offensichtlich, das den Männern missfiel, was sie tun mussten. Will war allgemein beliebt und seit langem als guter Unteroffizier bekannt. Ein weiterer Sergeant brachte die gefürchteten Neunschwänzigen Katzen. Sergeant Price flüsterte Howard zu:" Sei tapfer, mein Freund! Tu niemanden den Gefallen, zu schreien! Mach dem 33.ten keine Schande!"

Jamie Dullmore saß mit kaltem Blick auf seinem stolzen Andalusier und betrachtete das Spektakel offensichtlich sehr zufrieden. In diesem Augenblick hassten seine Leoparden ihn.

" Der Mann ist fertig für die Bestrafung!", meldete Robin Seward ihm traurig. Dann warf er einen Blick auf den Feldchirurgen des Regiments: "Ist der Mann in der gesundheitlichen Verfassung, um fünfzig Hiebe mit der Katze zu überstehen, Sir?"

Der junge Arzt nickte betrübt. Fünfzig Schläge mit der Neunschwänzigen waren eine leichte Bestrafung. Sie brachten niemanden um. Doch er bedauerte die Demütigung, die sie für einen guten Unteroffizier bedeuteten. Der Arzt hatte bemerkt, das sich auf Howards Rücken keine Narben einer früheren Bestrafung abhoben, obwohl der Mann mehr als vierzig Dienstjahre vorzuweisen hatte.

" Fortfahren, Sergeant MacGregor!", befahl Rob. Er musste sich große Mühe geben, um keine Schwäche in seiner Stimme durchscheinen zu lassen. Zwei Trommlerjungen sollten die Bestrafung durchführen. Seward jubelte innerlich, als er sah, wen sein ehemaliger Kamerad MacGregor für die Auspeitschung ausgewählt hatte. Es waren die beiden schwächlichsten Bürschchen des ganzen Regiments. Er musste sie, während die Offiziere ihr Kriegsgericht abgehalten hatten, beim Sanitätsdienst aufgetrieben haben. Ein dritter Trommler stand etwas weiter hinten. Er sollte den Takt angeben.

"Eins!", rief Mac Gregor. Die Katze hinterließ nicht einmal eine rote Spur auf Howards Rücken. Dullmore fluchte innerlich. Die Loyalität seiner Sergeanten untereinander würde möglicherweise alles verderben. Howard benötigte zumindest ein paar blutende Striemen, um General Gazan glaubwürdig den Deserteur vorlügen zu können.

"Zwei!", rief MacGregor. Wenigstens eine Rötung der Haut wurde sichtbar. Jamie atmete auf. Das Gesicht von Howard verzog sich leicht. Es war weniger Schmerz, als Erstaunen. Oberst Dullmore befand sich genau vor ihm. Er hatte in den Augen von Wellingtons jungem Protegée etwas ganz Absonderliches bemerkt - Besorgnis.

Mit einiger Mühe verursachten die beiden schwächlichen Trommlerjungen im Verlauf von fünfzig Schlägen ausreichend Risse in Howards Haut, als das sein Rücken blutete. Das Regiment sah der Bestrafung betrübt zu. Lediglich einige, kluge Köpfe bemerkten, wie kraftlos die Trommlerjungen doch zugeschlagen hatten und wie oberflächlich die Verletzungen auf Howards Rücken waren. Sie dachten sich, dass der alte Sergeant MacGregor ein ausgekochter Fuchs war, der diesen verdammten, hochnäsigen, jungen Obersten ganz gehörig hereingelegt hatte. Mit ein bisschen Glück behielt Howard nicht einmal Narben. Ein Eimer kalten Wassers wurde über den Rücken des Bestraften geschüttet. Robin Seward befahl dem Regimentsarzt, die Verletzungen gut zu versorgen und den Sergeanten zu verbinden. Ein Stabsoffizier aus Lord Wellingtons Hauptquartier kam ins Lager geritten. Er trieb sein Pferd bis zu Oberst Dullmore:" Sir, der General befielt, dass man ihm den Bestraften schickt. Sie sollen sich gleichfalls melden. Es geht um die Degradierung!"

Jamie nickte kalt. Dann wandte er sich an den Arzt:" Versorgen Sie den Rücken! Der Mann soll sich waschen und seine Uniform anziehen. In einer halben Stunde hat er sich im Hauptquartier zu melden!" Er zog seinen Andalusier herum und galoppierte in Richtung des Landgasthofes von Subijana Morillos. Trommlerjunge Meadows saß, an ein Wagenrad gefesselt, weinend im Lager der 33.Infanterie. Die beiden Soldaten, die ihn bewachten, hatten aufgegeben, ihn zu trösten. Es half einfach nichts. Sobald die Schlacht mit den Adlern geschlagen war, würde man dieses Kind an irgend einem Baum aufhängen. Es war grausam und ungerecht. Sie konnten nicht glauben, dass Tommy gestohlen hatte.

Als Sergeant Howard etwas später mit verbundenem Rücken und hängendem Kopf Lord Wellingtons Hauptquartier betrat, fand er dort zu seinem großen Erstaunen nur den General, Pater Jack und Oberst Dullmore vor. Jamie verriegelte die Tür fest, nachdem er eingetreten war. Um einen groben Holztisch standen vier Stühle. An jedem Platz stand eine Tasse mit heißem Kaffee.

"Howard, nehmen Sie bitte Platz!", bat der General ihn freundlich. Der Sergeant verstand gar nichts mehr.

"Diese Komödie, die wir eben mit Ihnen spielen mussten, sie tut mir leid!", eröffnete Oberst Dullmore das Gespräch, "Doch die Franzosen haben auch in unserem Lager Augen und Ohren! Wir konnten Sie nicht früher einweihen! Vater Jack hat das Pulverhorn und die Munition aus Ihrem Tornister entfernt und meine Börse in den von Trommler Meadows gelegt! Lord Wellington hat einen besonderen Auftrag für Sie beide! Tommy darf es nicht erfahren! Seine Angst vor der Hinrichtung und seine Jugend werden der einzige Schutz sein, den Sie haben - außer den blutigen Striemen auf Ihrem Rücken!"

Howard war ein kluger Kopf. Er begriff schnell, welchen Zweck der Oberkommandierende und sein Chefspion verfolgten. Man wollte eine Legende schaffen, die auch für den Feind glaubwürdig war. Die Adler hatten nie verstanden, dass König Georgs Soldaten hinnahmen, wegen irgendwelcher Verfehlungen bis aufs Blut geprügelt zu werden. Und die echte Angst vor dem Strick überzeugte auch einen hartgesottenen Frosch davon, dass sein britischer Gegner den Fahnen wirklich den Rücken gekehrt hatte.

" Will, es war wirklich nicht möglich, Sie vorher einzuweihen! Ihre Mission ist von äußerster Wichtigkeit für den morgigen Tag! Aus diesem Grund habe ich Oberst Dullmores Vorschlag akzeptiert, den besten Unteroffizier des 33.ten loszuschicken! Sie kennen das Risiko !", Arthur hatte eine Karte hervorgeholt und vor dem Sergeant-Major auf den Tisch gelegt," Sehen Sie hier die Brücken über den Zadorra? Etwas weiter unten am Fluss liegt das Dorf Subijana de Alava! Wir müssen es schnell nehmen, um die Übergänge zu beherrschen. General Gazan muss glauben gemacht werden, dass ihm keine Gefahr droht und dass ich mit einem großen Teil des Feldheeres gen Norden, auf Bilbao zu, abmarschiert bin! Verstehen Sie?" Er sah den Unteroffizier beschwörend an.

Howard atmete schwer. Natürlich verstand er den General. Doch warum hatte man gerade ihn und den kleinen Tommy für ein solch gefährliches Unterfangen ausgewählt? " Mylord Wellington, ich habe begriffen! Ich möchte nur......."

" Sie möchten verstehen, warum gerade Sie und Meadows gehen müssen!" Der Ire sah seinen alten Sergeanten nachdenklich an," Weil Sie ein Mann sind, bei dem ich einhundert Prozent sicher sein kann, dass er die Nerven nicht verlieren wird! Weil ich weiß, dass Sie eine List finden werden, um wieder in unsere Linien zurückzukehren! Weil ich glaube, dass der kleine Tommy Ihnen vertraut, wie seinem Vater! Weil ich annehme, dass er ihnen folgen wird, wenn Sie seine Stricke lösen und weil ich darauf hoffe, dass die blanke Angst in den Augen eines Vierzehnjährigen, dem der Strick droht, General Gazan davon überzeugen wird, das Sie die Wahrheit sagen! Die Franzosen haben große Informationsprobleme. Josephs Dispositionen beweisen mir, wie verwirrt er ist. Verwirren wir ihn noch ein bisschen mehr! Es wird vielen Ihrer Kameraden aus General Hills Divisionen das Leben retten ......"

" Wusste Major Seward etwas, Mylord! Wenn ich mir diese Neugier erlauben darf!" Howard und Rob waren schon seit langen Jahren Freunde. Der Unteroffizier hatte diese Frage einfach stellen müssen.

Arthur lächelte ihn an und schüttelte leicht den Kopf:" Nein, Will! Robins Empörung, seine glühende Verteidigung des kleinen Tommy, all das verstärkt Ihre Legende! Wir haben ihn selbstverständlich nicht eingeweiht. Oberst Dullmore und ich, wir konnten nur darauf hoffen, das Major Seward handelt, wie eben nur Major Seward handeln kann! Wir haben vermutet, das er Sergeant MacGregor befehlen wird, zur Vollstreckung einer Strafe, die er als ungerecht empfindet, die schwächlichsten der Trommlerjungen abzukommandieren. Niemand wollte dass unser Doppelagent irgendeinen Schaden nimmt. Aber ein paar echte Striemen waren trotzdem notwendig!"

Howard sah den Oberkommandierenden lange an. Seit zwanzig Jahren kämpften sie Seite an Seite:" Verdammt Mylord! Sie hätten es mir ruhig sagen können!" Er hätte das große Spiel auch ohne die große Komödie vom Morgen mitgemacht. Wegen der paar blutigen Striemen auf seinem Rücken hätte man sich eben geeinigt! Irgendwie war er auf den Iren wütend.

Lord Wellington hatte einiges Verständnis für seinen bewährten, alten Sergeanten, doch er wusste nur zu genau, das der Mann zu ehrlich war, um einen Schauspieler abzugeben: "Vertrauen Sie mir, Will! Dieser Weg war der Bessere, selbst wenn Sie um der Sache Willen einige schlimme Stunden verbracht haben! Im Namen der Himmels, weihen Sie bloß Jung-Meadows nicht ein! Ich will ihn lebend und unversehrt wiedersehen! Es ist besser, wenn er noch ein bisschen weiterzittert!" Der General gab Jack Roberston ein Zeichen. Der Benediktiner holte einen Krug und einen Pinsel von einem Tisch: " Ziehen Sie den Uniformrock aus! Wir müssen mehr Blut auf ihren Verband zaubern! Oberst Dullmore, trennen Sie alle Sergeantenstreifen ab! Der Oberkommandierende war über die Disziplinlosigkeit eines altgedienten Unteroffiziers so empört, dass er ihn in die Ränge zurückgestoßen hat!" Während Pater Jack, Howards Verband mit Blutflecken überzog, erklärte er ihm die weitere Vorgehensweise.

Beim Abendappell erfuhr die 33.Infanterie von Oberst Dullmore, das die Hinrichtung des Diebes Meadows auf nach der Schlacht mit den Franzosen verschoben wurde. Danach gab er bekannt, das Sergeant-Major Howard von nun an nur noch ein einfacher Soldat war und all seine Privilegien verwirkt hatte. Der Offizier gab sich große Mühe, sehr laut zu sprechen, damit auch der letzte Zivilist, der beim Tross des Regiments herumlungerte, jedes einzelne seiner Worte klar und deutlich verstand. Howard nahm die Demütigung mit hängendem Kopf hin. Auf dem Rücken seines Uniformrockes waren deutlich feuchte Spuren sichtbar. Manch einer der altgedienten Leoparden wunderte sich, wie fünfzig so vorsichtig administrierte Hiebe mit der Neunschwänzigen solch großen Schaden hatten anrichten können. Bei den Worten von Oberst Dullmore ging ein leises Murren durch die Ränge. Die Soldaten waren sichtbar ungehalten über die unbegründete Härte und Grausamkeit, mit der ihr neuer Oberst vorging. Bedrückt trollten sich alle nach dieser Ansprache ihres Kommandeurs zum Abendessen. Es war vielleicht ihr Letztes. Lord Wellington hatte seine Befehle ausgegeben. Am nächsten Tag wollte er König Joseph Bonaparte angreifen. Howard mied seine Kameraden und schlich mit betretener Mine zu dem Trosswagen hin, an dem der junge Meadows festgebunden war. Der Trommler wurde nicht einmal bewacht. Wie sollte ein Kind, das von zwei soliden Stricken an einem soliden Wagenrad festgehalten wurde schon weglaufen. Howard setzte sich neben Tommy ins Gras, während die anderen sich daran machten, ihr Abendessen vorzubereiten. Man hatte Befehl erteilt, keine Feuer zu entzünden, um feindlichen Spähern keine Anhaltspunkte über die alliierten Nachtlager zu geben. Und Oberst Dullmore hatte sorgfältig darauf geachtet, das ein fünfzig Meter breiter Streifen um Subijana Morillos in dieser Nacht vor der Schlacht unbewacht blieb.

Howard hatte keine Probleme, Meadows dazu zu überreden, mit ihm zusammen fortzulaufen. Der Junge hing an dem Sergeanten, wie an einem Vater! Er hatte niemanden bestohlen und trotzdem wollte man ihn aufhängen. Außerdem, welchen Grund hatte er noch, bei der 33.Infanterie zu bleiben, wenn sein bester Freund nicht mehr da war. Zwischen den Leoparden und den Adlern lagen wenig mehr, als fünf Meilen. Nachdem Howard und Meadows die britischen Wachposten hinter sich gelassen hatten, rannten sie in einen nahen Wald. Der Sergeant packte Tommy am Arm: "So mein Kleiner, jetzt wirst Du Deine Uniformjacke verkehrt herum anziehen, damit die Frösche uns nicht mit Spähern verwechseln! Das tun Deserteure nämlich!" Er tat das selbe. Dann befreite er den Trommler von seinem unbequemen Lederkragen," Na los, wir müssen weg, bevor die anderen etwas bemerken!" Kurz vor Mitternacht stießen sie auf die Vorposten der Vorhut von General Gazan. Sie hatten Glück. Niemand schoss auf sie. Howard hatte laut gerufen:" Ami, Ami! Deserteur! " Das waren so ziemlich die einzigen französischen Worte, die er kannte. Die Wachposten hatten ihm und Tommy zwar kräftig die Gewehrläufe in den Rücken gestoßen, doch sie hatten wenigstens nicht abgedrückt. Man beförderte die beiden Leoparden zum nächsten Offizier. Der Mann sprach kein Englisch. Doch Howard und Meadows gelangten zum nächsthöheren Dienstrang. Immer weiter und weiter wurden sie gestoßen und geschubst. Zwei Stunden später standen sie im Zelt des Comte de Gazan. Einer der Frösche hatte ausgezeichnet Englisch gesprochen! Howard hatte ihm die ganze Geschichte erzählt, die Sir Arthur ihm aufgetragen hatte. Zum Beweis hatte er den Uniformrock ausgezogen und dem Offizier seinen blutgetränkten Verband gezeigt. Tommy war von der Flucht, vom Kriegsgerichtsverfahren, von dem schrecklichen Todesurteil, das man über ihn verhängt hatte noch so aufgelöst gewesen, dass er die ganze Zeit, neben seinem großen Freund gestanden und geheult hatte. Er war gerade vierzehn, ein Kind!

Der Comte de Gazan hörte sich die Geschichte mit Hilfe des Übersetzers noch einmal an. Dann betrachtete er voll Mitleid den blutgetränkten Verband, der Howards Rücken bedeckte. Er hatte nie verstanden, wie die Briten ihre Männer so demütigen konnten. Auf der roten Uniform des Deserteurs sah er deutlich die Stellen, an denen einmal die fünf Unteroffiziersstreifen festgenäht gewesen waren:" Mon Dieu! Ce bâtard de Wellington! Comment peut-il traiter un homme de cette façon? Und das wegen eines Pulverhorns und sechzig Schuss Munition!" Er klopfte Howard mitfühlend auf den Rücken. Der Sergeant hatte den glücklichen Reflex, wie vor Schmerz zusammenzuzucken. " Pardonnez-moi, mon Brave! Ich hatte vergessen..." Der französische General wandte sich einem Adjutanten zu: "Lassen Sie einen Arzt nach dem Rücken diese Mannes sehen. Sorgen Sie dafür, das die beiden Briten zu Essen bekommen und bringen Sie sie zu einem Feuer, damit sie ausruhen können!" Dann setzte er sich an sein Schreibpult und verfasste einige Schreiben für die Truppen, die Subijana de Alava besetzten. Er befahl ihnen, bis zum Zadorra vorzurücken und das Dorf freizugeben. Lord Wellington hatte eine große Streitmacht gen Norden in Bewegung gesetzt. Er musste sofort Marschall Jourdan und den König informieren. Der Sepoy-General setzte dazu an, eine erneute Flankenbewegung durchzuführen, um der französischen Armee in den Rücken zu fallen.

Howard und der kleine Meadows saßen komfortabel an einem Feuer des 32.französischen Infanterieregiment. Die Frösche sprachen genau so gut Englisch, wie die beiden Leoparden Französisch. Doch dem zu trotz entwickelte sich bald eine angeregte Konversation, die mit Händen, Füßen, Gesten, Zeichnungen im Staub und anderen Hilfsmitteln geführt wurden. Es hatte sich herumgesprochen, das die Briten Tommy hatten hängen wollen. Die hartgesottenen, französischen Veteranen brachten ihr Unverständnis für diese üble Behandlung eines Kindes zum Ausdruck. Man drückte dem Trommler einen Apfel in die Hand, oder strich ihm über die Haare oder bedeutete ihm, das Monsieur le Général, le Comte de Gazan nicht grausam sei, wie dieser irische Satan Wellington. Meadows war so erleichtert darüber, dass er nun fort war von seiner 33.Infanterie und von Oberst Dullmore, der ihn aufhängen wollte. Deutlich zeigte er den Adlern seine Dankbarkeit für jedes ihrer guten Worte. Sergeant-Major Howard hatte das Gefühl, dass sie beide vorerst vor jeglicher Verdächtigung sicher waren. Sein Gehirn arbeitete schon hektisch daran, wie sie sich - sobald Sir Arthur angreifen würde - sowohl vor ihren neuen, französischen Feinden, als auch vor ihren eigenen Kameraden in Sicherheit bringen konnten, um das Ende der Schlacht abzuwarten und wieder in die britischen Linien zurückzukehren.

Copyright Peter Urban 61470 Heugon FranceNo part of this text may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing

from either the author or her agent. For inquiries, please sent an e-mail to: